Up until the 1980s, fashion in Lithuania was rigid and homogenous. While there were some variations for womenswear, menswear offered identical silhouettes and colours with only minor alterations. This lack of change was mainly because all clothing sold in Lithuania had to be approved by the government, with exceptions for home-made clothing. The Central Lithuanian Fashion House (CLFH) was founded in 1954: its mission was to control the design and production of clothes (Bartlett, 2010, p. 214).

The CLFH was the central institution to ensure fashions fitted Soviet guidelines. Designers in all three of the Baltic fashion houses were informed about the best Western trends and, as the Baltic States were geographically the closest to the borders of the USSR, they had better access to Western media through the black market. Despite this, all fashions had to undergo a lengthy approval processes.

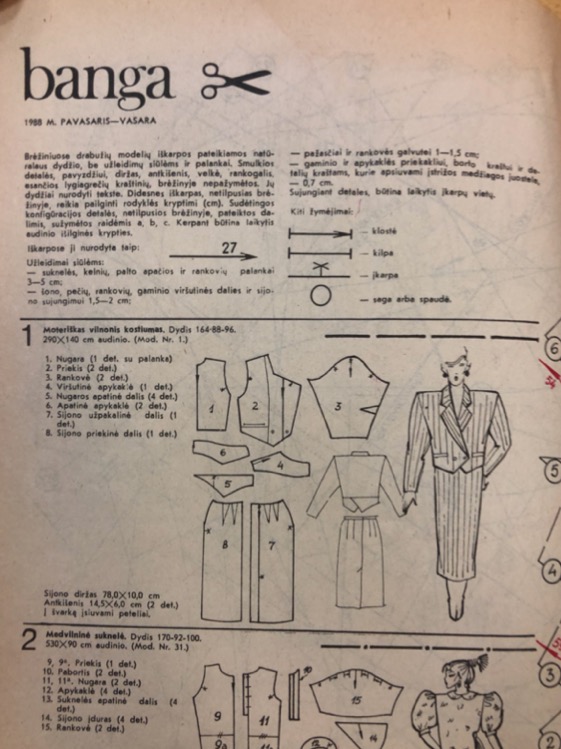

The magazine Banga (Wave) was first published in Vilnius in 1962. This magazine was the only fashion magazine in Lithuania at the time, making it an exclusive platform of fashion news in Lithuania. The magazine featured looks created by the Vilnius Fashion House, yet these were bespoke and unavailable in shops. As a compromise, some issues of Banga included paper patterns, from which readers could make their own dresses (Figure 1).

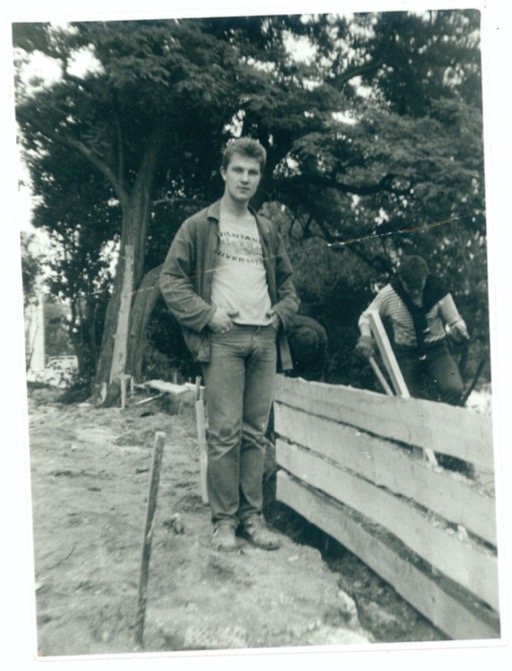

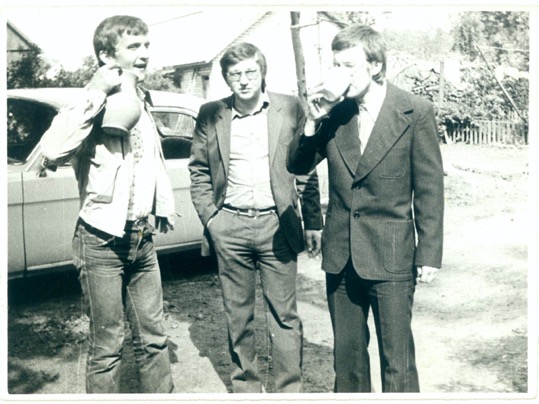

Trends such as the Mod style, which became popular in the West during the 1960s, were only promoted later within the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s through magazines such as Banga. Fashion trends were generally delayed by 10 to 15 years in the USSR, compared to foreign countries. Egidija Ramanauskaitė explains the appearance of the first subcultures in the late 1960s: ‘the first youth-based cultural movements appeared (...) as the first alternatives to traditional society and as an opposition to the Soviet ideology’ (2004). The waves that became mainstream next were ‘hippie groups’ and ‘rock music’ (Ramanauskaitė, 2004). Most Lithuanians desired jeans from the hippie culture, and men particularly wanted long hair and shaped moustaches. With the beginning of Perestroika, some other subcultures, such as rock and punk-rock, began growing in Lithuania: Perestroika then let youth express their fashionable selves without fear.

Lithuanian youth had little interest in the fashions available in shops, and the choice in markets was extremely limited. As the production of apparel was centrally planned and underwent lengthy approval processes, clothing was made to serve its utilitarian purpose, and was produced in limited amounts. As a result, few fashion trends were evident. However, younger, fashionable Lithuanians sought individuality rather than a uniform look, in order to stand out from the masses. Consequently, black markets of Western goods were established around the 1960s.

According to Dalija Kudarauskienė’s memories, fashions from abroad were often sent to Lithuania by emigrant relatives, especially those who had family in the United States. Clothing was also bought illegally by the very few Lithuanian artists, singers, sports teams, or scientists, who were permitted to travel abroad on contests or work trips. Sailors were some of the biggest sellers of foreign goods via seaside towns such as Klaipeda or Palanga. Once goods were shipped into Lithuania, they could be sold through physical black markets. Dalija recalled that garments were sold by spekuliantai (‘speculants’) or sold to friends or acquaintances on Sunday mornings in a secret section in the market of Plunge.

The most common items smuggled in from abroad were Levi’s or Wrangler jeans, sneakers, sports gear and clothing from Adidas, Nike, Reebok, Puma, and Montana brands, as well as makeup. Jeans were not sold in shops in the USSR, so they were highly desirable – anyone with jeans was considered fashionable and modern. A pair of jeans would usually cost 60-80 roubles in the black market; an average monthly salary of a worker would be 110-140 roubles. Therefore, jeans were an expensive product to stand out.

Raimundas Kudarauskas corroborated Dalija’s memories – explaining how he ‘would resell items brought by one of the basketball players of the national team’ (the interviewee refused to give away the name). Raimundas obtained these items from the player’s sister, which was done in order to protect the player from being dismissed from the national team, as it was an illegal activity. Raimundas would sell the items in a café in central Kaunas. He was known as a seller only to a very limited amount of people. If he did have anything to sell on the day, he would sell the items ‘away from the public view’ (Interview with Raimundas Kudarauskas).

“The most common items smuggled in from abroad were Levi’s or Wrangler jeans, sneakers, sports gear and clothing from Adidas, Nike, Reebok, Puma, and Montana brands, as well as makeup. Jeans were not sold in shops in the USSR, so they were highly desirable – anyone with jeans was considered fashionable and modern.”

The black market did not only consist of goods from abroad. ‘Corrupt behaviours were seen as secret, yet acceptable ways of gaining exclusive or limited goods’, Aldona Kudarauskienė claimed in our interview. Stealing from workplaces and selling goods for less than the official price, or obtaining them for free or for a small fee, was a highly common practice amongst workers in most industries. Aldona worked in A. Šaučiūnaitės’ jersey factory in Kaunas, Lithuania. She explained that she would bring ready-made items of clothing home with her in secret, yet she believes it was not stealing: this practise was commonly called kombinavimas (combining). Aldona shared her memories about kombinavimas:

Once I asked my colleague, what are you taking home today? She answered that she is not taking anything as she has enough money now. I told her she’s being silly and that she will spend her money soon, so she listened to me and stole some production for resale (Interview with Aldona Kudarauskiene).

This technique was common amongst regular workers, but managers and directors also undertook similar activities. However, the managers and directors of companies could take clothing in much larger quantities, as they were wealthy enough to own cars, so could transport fashions secretly, with more ease. Kombinavimas would often require bribing workers from other departments, either with money, pies, or in exchange for cover-ups of their own illegal activities. We could certainly call this an entire illegal economy, due to its wide extent. Because every single factory and shop was nationalised within USSR-controlled Lithuania, workers did not view this practice as causing personal harm to the owner of the business, as we might in a Capitalist economy.

“Kombinavimas would often require bribing workers from other departments, either with money, pies, or in exchange for cover-ups of their own illegal activities.”

In summary, I returned to my homeland of Lithuania to discover more about the imposed masculine ideals and strict fashion codes for men in Soviet-ruled Lithuania. I ended up becoming fascinated by the historical context and socio-political landscape of this time, so undertook a detailed analysis of the multifaceted cultural factors that contributed towards Lithuanian fashionable ideals. The oral history interviews with family members allowed me original insight into their personal experiences and memories of this time, and my dissertation engaged with the field of Lithuanian fashion history to challenge preconceived ideas around Lithuanian masculinity. Ultimately, my work suggested that there is significant scope for continuing with this subject, as not enough has been researched and written about this area.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, D. (2010) 'Snapshot: Lithuanian Urban Dress, 1940s to Twenty-First century', in Bartlett, D. (ed.) Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: East Europe, Russia, and the Caucasus. Oxford: Berg, pp. 214-215.

- Interview with Raimundas Kudarauskas (aged 52) (2019).

- Interview with Aldona Kudarauskienė (aged 85) (2019).

- Ramanauskaitė, E. (2004) 'Subculture: Phenomenon and Modernity. Kaunas: VMU Press.

All I want is...

All I want is...