Gender inequality is a concerning problem in the fashion industry. The Design Council’s 2018 report stated that ‘78% of the UK’s design workforce is male’. Moreover, women are less likely than men to be in senior roles, with only ‘17% of design managers being female’ (2018, p. 7). Furthermore, and perhaps quite shockingly, this situation has developed ‘despite women making up 63% of all students studying creative arts and design courses at university’ (2018, p. 53).

These surprising statistics suggest that while design is an industry that has historically been considered feminine, women within the industry are not respected, or treated equally. The above data also unveils a pattern of women being associated with craft, whilst men, argues sociologist Christine Hughes, are often associated with the higher arts and design industries (Hughes, 2012, p. 446). Even ‘qualities such as creativity and talent are socially constructed characteristics often associated with privileged masculinity’, argued Roszika Parker, in her seminal 1984 book, The Subversive Stitch (2010 [1984], p. 218). It is clear that historically formed social stereotypes around femininity and masculinity influence women’s opportunities in the fashion industry today.

While one might suppose that women would dominate the field of fashion design for women, in fact, women designers have been in the past and continue today to be outnumbered by male designers in the field of fashion design for women (Crane, 1999, p. 61).

“historically formed social stereotypes around femininity and masculinity influence women’s opportunities in the fashion industry today.”

Diana Crane’s suggestion above, is still a reality of the modern fashion industry. Recent statistics show that ‘women make up more than 70% of the total workforce yet hold less than 25% of leadership positions in top fashion companies’ (BoF.com, 2015). In Business of Fashion (BoF) articles, stereotypical characteristics of a designer being described as original, creative, powerful, and dominant, are mentioned as usually linked with men, rather than women. Writing for the journal Design Issues in 1984, Cheryl Buckley pointed to the area of dressmaking as being considered a feminine industry. However, Buckley also noted that fashion design ‘has been appropriated by male designers who have assumed the persona of genius - Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, and, more recently, Karl Lagerfeld’ (1986, p. 5). This shows how deeply-rooted the perceptions of gender and its inequalities are, and how relevant they remain in the fashion industry.

Figure 1. Chanel (2019)

Figure 2. Dior (2019)

There is another intriguing relationship between luxury fashion brands, women, and craft. It has become a noticeable trend of luxury fashion houses to post videos on social media platforms to show the process of making the collection after each fashion show during fashion weeks. Brands such as Chanel and Dior released videos of the design process from the concept to the final show (See Figures 1 and 2). Often, the focus of their videos is the craftsmanship and handmaking processes that go into the garments and accessories of the collection, showing the skilful and time consuming techniques of embroidery, printing, and hand-finishing.

In this way, fashion brands try to show how much time and skill is required to create their garments, which then has the consequence of raising the brand’s fashion and craft to the level of higher arts. Furthermore, most of the videos show that production of the collections is located in Paris – the home city of Haute Couture. Correlations can therefore be made between the historical and stereotypical norm of women making crafts at home, and women creating collections by hand in Paris. While craft, and craftswomen’s skills in particular, are being used for advertising purposes, gender inequality in the fashion industry is still a pressing problem. Respect for craft and greater equality for the women behind this craft, is still to be reached.

“While craft, and craftswomen’s skills in particular, are being used for advertising purposes, gender inequality in the fashion industry is still a pressing problem. Respect for craft and greater equality for the women behind this craft, is still to be reached.”

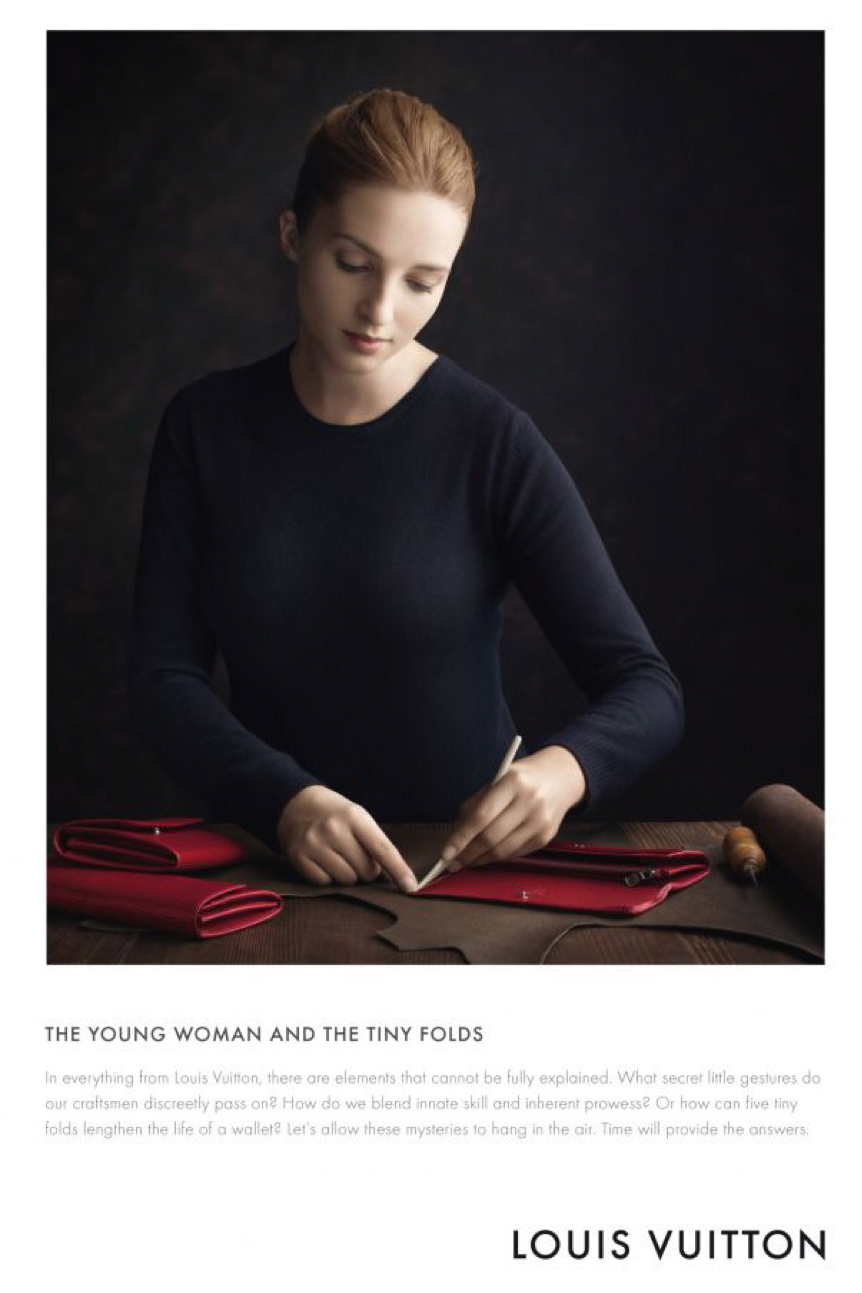

Another interesting example of craft being used as a medium to advertise a fashion house is Louis Vuitton’s craftsmanship campaign in 2010 (Figure 3). The brand released a series of images of women and men making Louis Vuitton fashion products by hand. However, this campaign was in fact banned in 2010 by The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) for being misleading. The ASA argued that Louis Vuitton created the possibility for customers to believe that their products are hand-made, when in fact they are not (Brownsell, 2010). This example from Louis Vuitton demonstrates how the use of craft as a medium for advertisement must be more subtle (and accurate). This also helps us to understand the reason behind the growing popularity of craft videos being released by luxury fashion brands.

In conclusion, there is still a long way to go to reach gender equality in the fashion industry, and for craft to be recognized as a respectable niche. During the course of my research I became fascinated by the trend of craft videos used by major fashion houses, and their decision to let people into the inner workings of these processes to create collections through craft. It is interesting to see how women, working in the lowest positions of the fashion industry, can become a tool for advertising and a way of promoting fashion as a high end, high-art, and valuable, design industry.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, O. (2017) ‘A Woman's Work: How Women Can Get Ahead in Fashion’, Business of Fashion. Available here. Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Brownsell, A. (2010) ‘Louis Vuitton “Hand-Made” Campaign Falls Foul of ASA’, Campaign. Available here. Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Buckley, C. (1986) ‘Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design’, Design Issues, 3(2), pp. 3–14.

- Chanel (2019) Chanel’s preparation of embroideries for Metiers d’art 2019/20 show. Available here. Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Crane, D. (1999) ‘Fashion Design and Social Change: Women Designers and Stylistic Innovation’, Journal of American Culture, 22 (1), pp. 61–68.

- Design Council (2018) ‘The Design Economy 2018: The State of Design in the UK’ Available here. Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Dior (2019) Dior in the making of Spring-Summer 2020 women’s collection. Available here: Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Hughes, C. (2012) ‘Gender, Craft Labour and The Creative Sector’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 18 (4), pp. 439–454.

- Parker, R. ([1984] 2010) The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and The Making of The Feminine. New ed. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Pike, H. (2016) ‘Female Fashion Designer are Still in The Minority’, Business of Fashion. Available here. Accessed 13.12.2019.

- Unknown (2015) ‘How can fashion develop more women leaders?’, Business of Fashion. Available here.

All I want is...

All I want is...