This article comes from a section of my dissertation, where I discuss the process and approach of hybridity and its relationship in fashion, that could help in the revival of Malaysian traditional arts and culture. Cultural heritage has always been a proud commodity for Malaysia. This country is known for its culture and the traditions that come with the diversity and richness of race and religions. The awareness of this cultural diversity resembles that of a living embodiment by Malaysians in evolving a distinguished culture that is rare and vibrant through its resourcefulness and unconventionality. As mentioned by Othman:

Such diversity adds to the repertoire of modes of cultural expressions that can be included under rubric of ‘Malaysianess’. It is precisely the complexity and flexibility which makes up the vitality of Malaysia’s cultures. It is the importance that makes up the national identity from history, culture and unique traditions (1994, p. 13).

What is the Malaysian Culture?

In 1957, Malaysia became independent of British rule. Peninsular Malaysia (formally known as the Federation of Malaya) inherited an economy constructed by British colonial business. Malaysia had to be strategic in developing ways to modernize, without compromising the fragility or ethnic balance of the population, which included Indians, Chinese, Kadazans, Ibans and other minorities, including the Orang Asli (native people). Othman points out that ‘the burgeoning traffic of trade brought with it edifying cultural influences which were assimilated and accepted by local people. This cultural inheritance, however diverse became harmonized to form a common heritage which ensured a historical and cultural continuity’ (1994, p. 15).

Crossovers among diverse cultural groups within a community is uplifted by interculturalism. This helps to promote the socialization of nations from diverse ethnic backgrounds as a technique to go against racism, and to overcome prejudice through interculturalism. This also opens harmonious interchange between cultures in the formation of a new culture, while seeking constructive alternatives for the future. (Nor, 2007, p, 109). Rojak, which is a well-known typical Malaysian dessert, is a term that is used as an expression which displays the contribution of each and every culture that builds the Malaysian culture.

The Disappearance of Malaysian Traditions

Malaysian traditions today are in some ways disappearing. It is perhaps unsurprising that these traditions and customs are neglected and forgotten, and this has been attributed to modern technology and social media. Furthermore Malaysia, ‘as with all countries that modernize and progress technologically, local nuances, languages and art forms get swallowed up by the tide of globalization’ (Petra, 2018).

To prevent this disappearance, in 1979 the Malaysian Handicraft Board was re-established as the Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation (MHDG). This Board aims to support and promote communities of passionate crafts people that are resilient, spirited, and ambitious. The Board exists so that these crafts are able to demonstrate intellectual inquisitiveness, and so they can produce a compelling craft industry for markets both locally and globally, while maintaining aesthetic values through commercialization. It is also important that these companies are able to make feasible crafts in an economic way, that is both current and desirable (Malaysia Yearbook, 1996, p. 483).

Studio Practice

For my final major project, I examined the traditional Malaysian arts and culture. I researched The Wau, otherwise known as the Malaysian kite, which is derived from the resulting sound of the arc that attaches to the wau. As the wau is lifted into the air, the ibus leaves that are mounted on the arc produce a sound like “wau”, in rhythmic form. There are numerous versions of Malaysian kites that are associated with the various states in the country. Each kite is believed to have its own meaning, represented by different symbols. Wau have been a traditional pastime, as they were played with by laborers such as farmers and fishermen, as a way to relieve stress after a working day. Malaysian kites then became a form of entertainment for all ages, and competitions were held. The tournament of Wau was judged based on several aspects, mainly the authenticity of the creation, the pattern of creation, the shape, color, and size. However, this tradition has faded with the disappearance of the older generation.

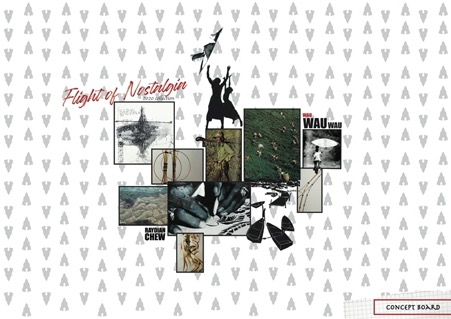

Flight of Nostalgia is my 2020 Womenswear Capsule Collection. My collection revolves around the concept of Wau, dissecting the ideology of the Malaysian kite, making its intricate motifs and bringing elements with emphasis in contemporary designs. Inspirations for the beauty of Malaysian crafts are then broken down into several perspectives: from the texture of fabric manipulation; to 3D construction, incorporated into the collection.

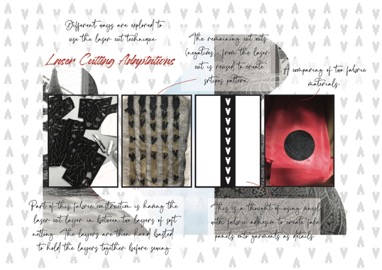

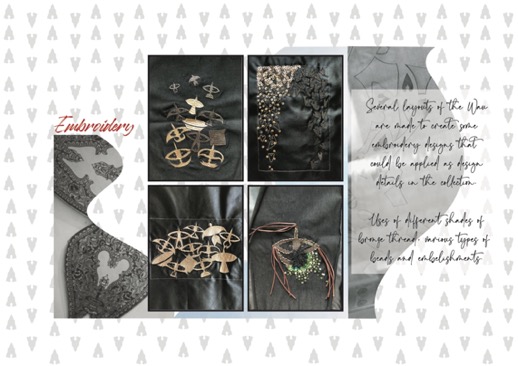

In terms of success in flying, the framework is the most important part of making a kite (Leigh, 2000, p. 105). However, the ‘bones’ of a completed kite are no longer visible when the kite is covered with layers of decorated paper designs. The idea for my final collection was inspired by this, as well as the 3D silhouette construction that can be seen in my explorations which are based around the boning used in corsetry. The shapes are abstract, draped within stand works that shows the emphasis in the importance of a framework while combining them with contemporary designs, reflecting the covered layers of decorative paper designs. Further adaptations in the collection include fabric construction, which was created with laser cutting and digital prints as other key features in the collection, in addition to embroidery. This constitutes the commercial part of the collection.

My approach towards reviving the Malaysian tradition is based on the application of the intricacies and details around craft, by making this the central story behind my collection. This inclusion of traditional Malaysian craft details become a way of sending a message to the consumer, and underlying the importance of engaging with cultural traditions. The need and importance to value one’s heritage, tradition, craft and quality should be encouraged so that we remember where we came from. Don’t let traditions be like the kite’s flight, a beautiful experience which can end ever so abruptly by just letting the string slip through our fingers.

Bibliography

- Pre-collection looks from Flight of Nostalgia (Chew, S. L., 2020) Unpublished.

- Fern, C., Low, C. C. (2012) Malaysian Culture: Views of Educated Youths About Our Way Forward. Cambodia: Proceedings of the Third Internatioanl Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences.

- Jenks, C. (1993) Culture. London: Routledge.

- Leigh, B. (2000) The Changing Face of Malaysian Crafts ‘Identity, Industry, and Ingenuity. Malaysia: Oxford University Press.

- Malaysia Yearbook. (1996). Kuala Lumpur: Berita Publisbing Sdn Bhd.

- Nor. M. A. M. (2007) Convergence of Diverse Cultural Backgrounds as Discourse of Contemporary Dance in Malaysia, Mohd Anis Md Nor (ed.) Dialogues in Dance Discourse: Creating Dance in Asia Pacific. Kuala Lumpur: World Dance Alliance-Asia Pacific, Cultural University of Malaya and Ministry of Culture, Arts and Heritage Malaysia.

- Othman, D.H.S., Salinger, H. R., Khoo, J. E., Ali, M. K. H., Regis, P. and Yeoh, J. L. (1994) The Crafts of Malaysia. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

- Petra T. M. (2018) ‘A look at the dying traditions of Malaysia as the country lurches forward’, Lifestyle Asia, 7 June. Available here. (Accessed: 13 February 2020).

All I want is...

All I want is...