‘Nothing signals the arrival of a new generation so surely as the fact that the previous one is shocked by its influences’. (100 Fashion Designers 10 curators, 2013, p. 4)

Massimo Osti (1994-2005) is an Italian designer, born in Bologna, who dedicated his life to the experimentation and creation of a new type of fashion. He studied graphic design, and in the 1970s, he created a range of t-shirts with innovative printing techniques like silkscreen and four-color process, both of which are widely used nowadays. During the 1980s, Osti experimented with materials and textile development, as well as creating different types of dyeing techniques. In 1987, Osti presented ‘Rubber Flax and Rubber Wool’: linen and wool with a thin rubber coating which made the fabric waterproof. After this, Osti went on to create the brands Stone Island and C.P. Company, both of which shared the same principle: avoiding seasonal collections, and instead focusing on creating garments that would last a lifetime.

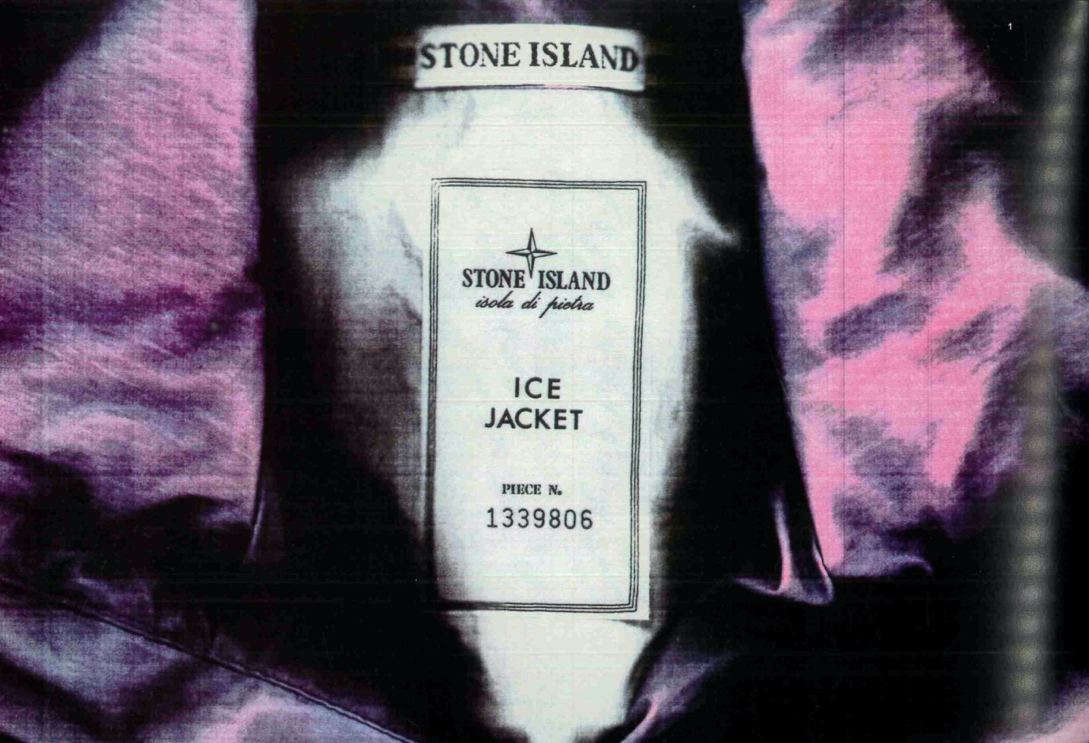

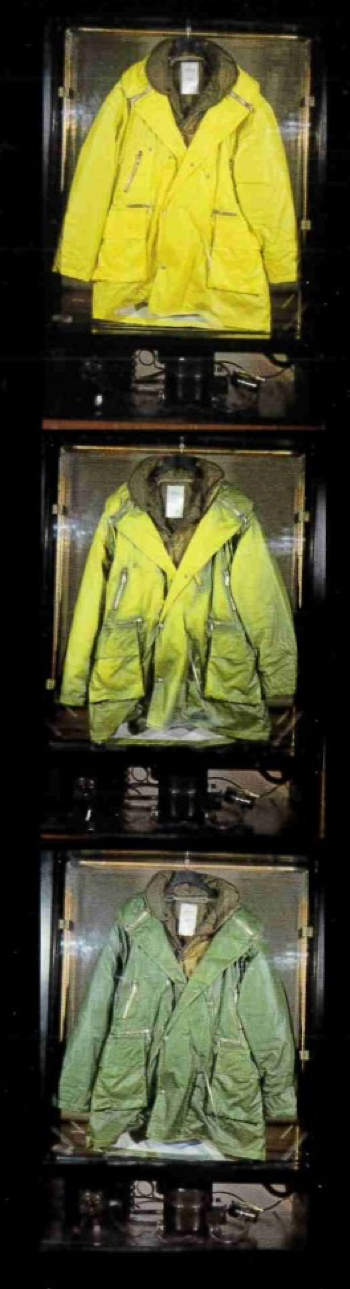

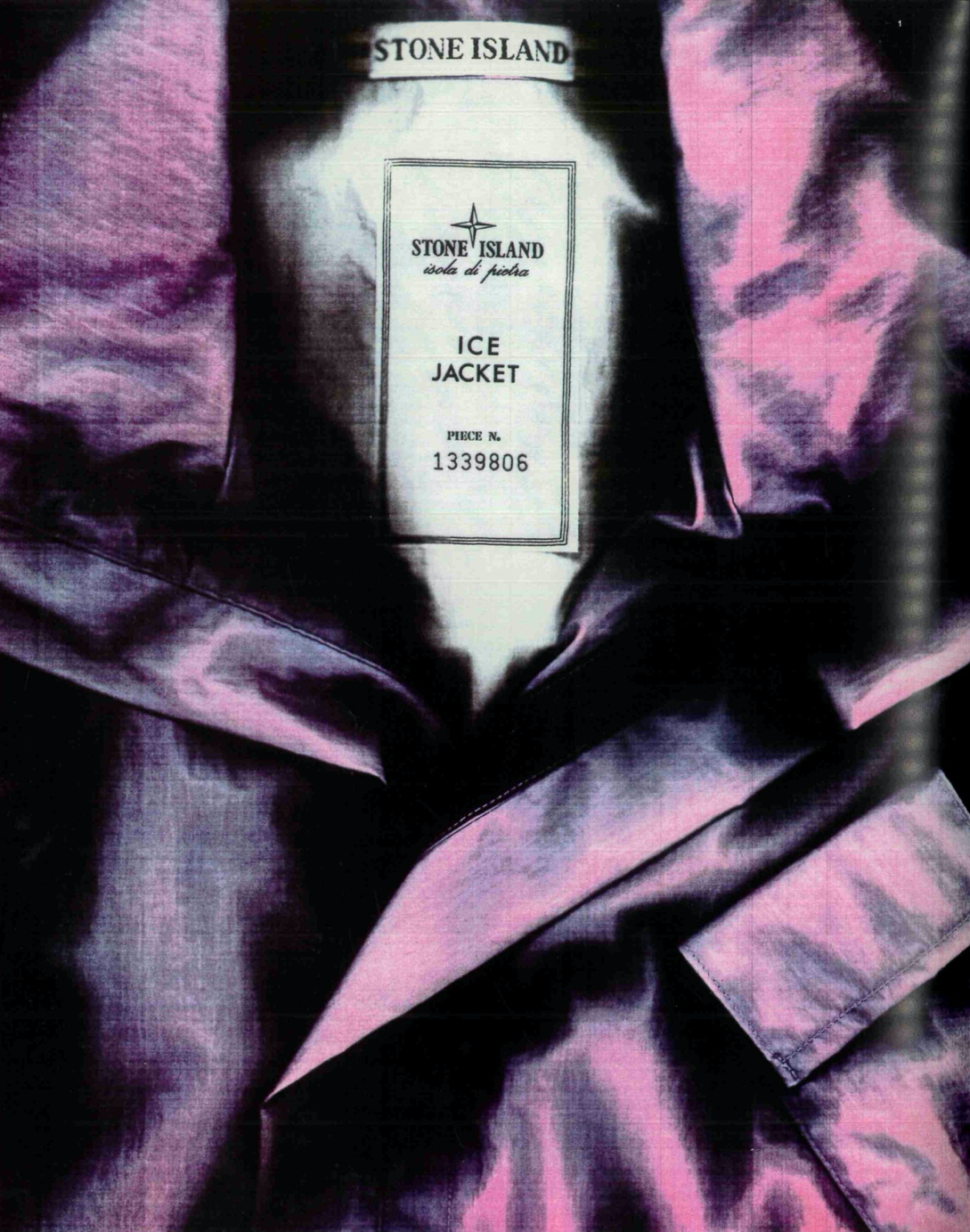

The Ice Jacket (1987) (Figures 1 and 2) was the first product that joined together Osti’s technological advances in one garment. The jacket was made from liquid crystals that created a fabric which could change colour, depending on temperature. The jacket inspired a collection made with this material, which became popular with celebrities and high-profile clients such as Olympian skier Alberto Tomba, and Prince Rainier of Monaco (Facchinato, 2016, p. 56). Osti continued to develop fabrics such as Cool Max throughout his career. This was a fabric that makes the moisture of the body stay outside of the fabric. He also developed Mag Defender: a fabric that protects the wearer from magnetic fields, and Steel, which is a highly resistant fabric from cuts and tears (Facchinato, 2016, p. 14)

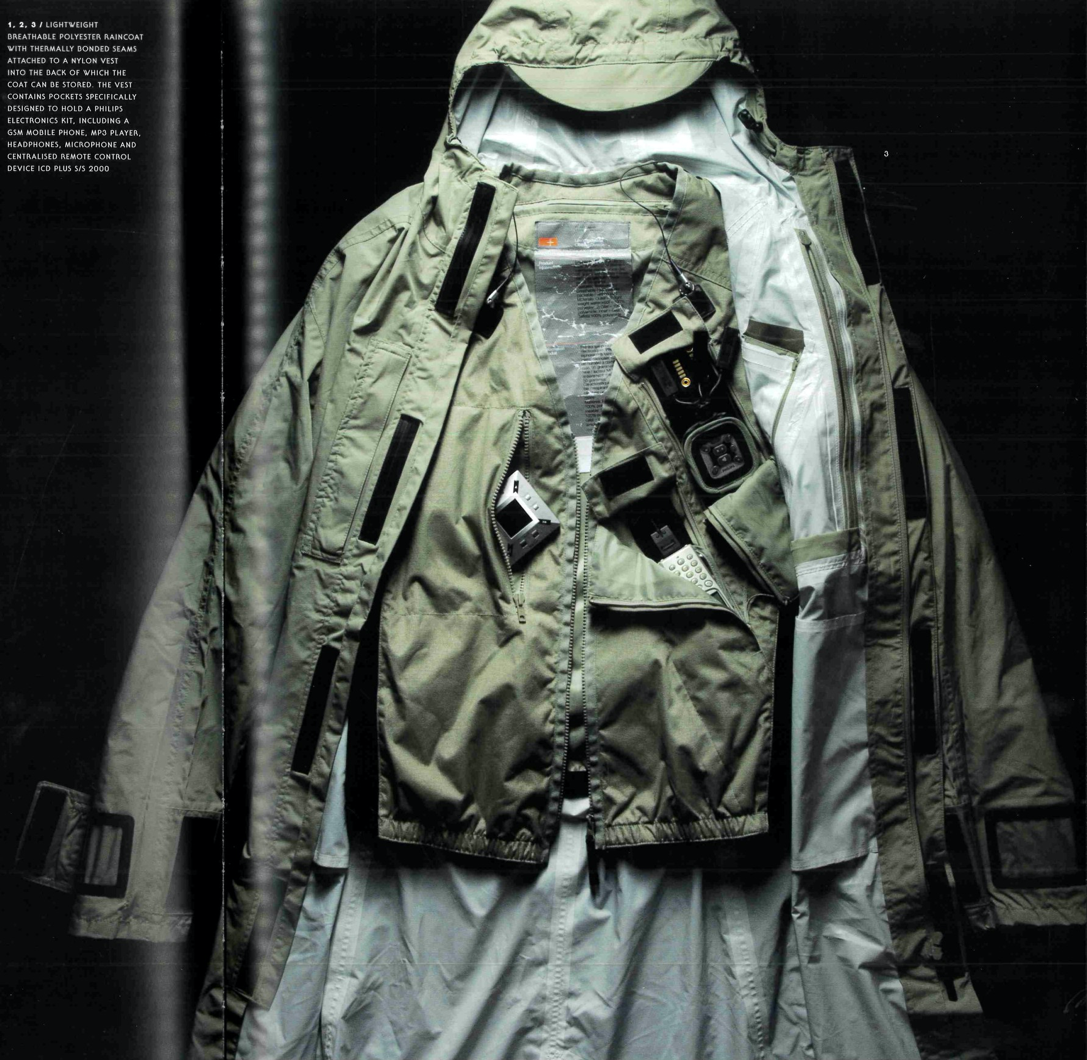

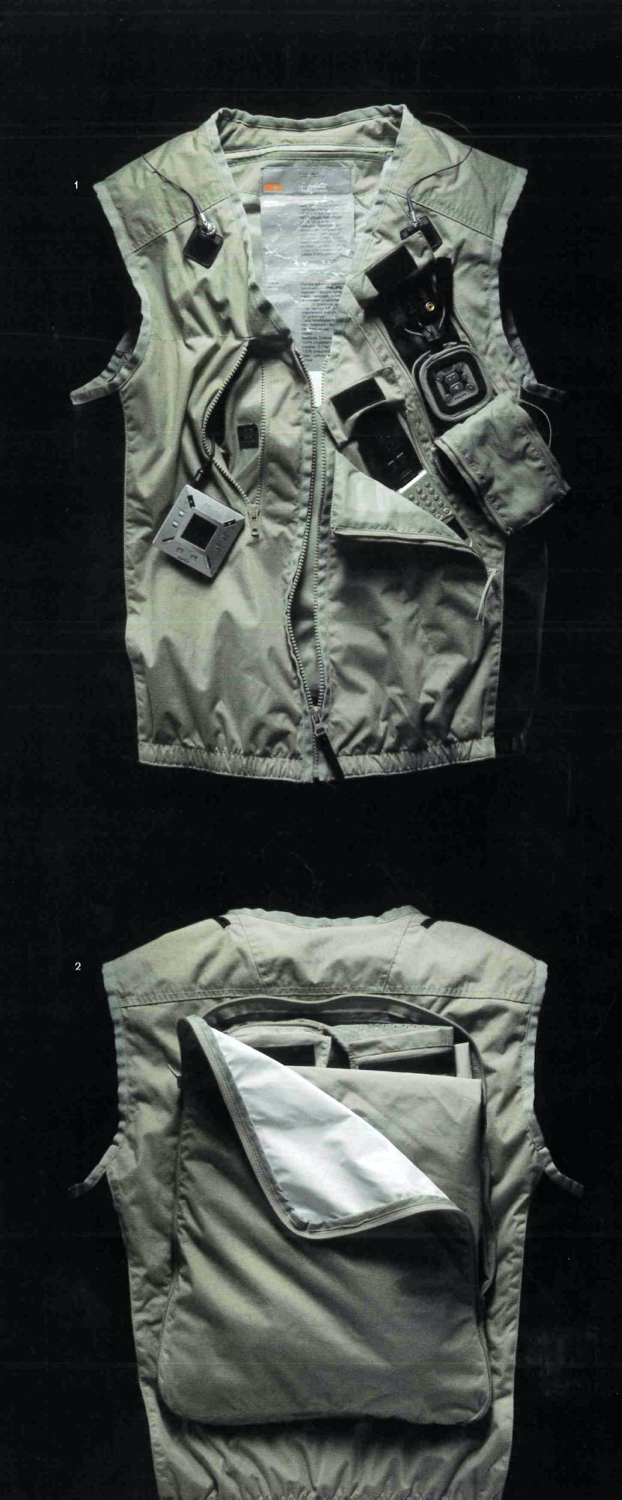

In 2000, Osti undertook a collaboration with Phillips and Levi´s. The result was the ICD+ line: a collection of high-performance, technical outerwear, seen in figure 3 and 4. These garments could be equipped with a mobile phone, an MP3 player, accompanying headphones, and a microphone, all of which were wired into the garment itself. This product was ground-breaking in that it was the first commercial offering where the garment was purposefully designed to house and fully integrate a variety of consumer electronics.

A few of the garments from the ICD+ collection are stored in the Westminster Menswear archives. I had the opportunity to visit the archives to examine them first-hand. One of the garments I analysed was a sand-coloured, hooded jacket from 2000 with a variety of wearable technology features. All the trimmings were black to contrast with the sandy main colour. The openings were double secured with a zip and Velcro tabs, and there was Velcro on the cuffs, which made them adjustable. The jacket lining was black mesh with taped seams. There were two curved large pockets on the front, closed with zippers, where the user could connect their phone and MP3 player to the jacket, with room for other objects to store inside the large pockets. All the wiring was hidden inside the garment, which gave the jacket a clean cut and simple silhouette. The earphones were wired into the hood, which is a design that has since been used for contemporary products. All the wires were easily removable, making it completely safe to wash, if necessary. The jacket’s design also included a practical way of being stored, by folding it into the two main pockets, so that it could become a shoulder bag. In appearance, this sandy jacket looks like any outerwear jacket. However, once I started opening the pockets, feeling the integrated wires, and noticed the connectors, I realised it is something else entirely.

The way a wearer could use this jacket was confusing, as it did not seem to come with any instructions. While looking for more instructions about how to use it I found a small description on the webpage of the archives: ‘A central control module connects all the devices through the unified remote control to allow the wearer to switch between them and control their separate functions’ (Westminster Menswear Archives, 2020). Apparently, when someone purchased the jacket, they were given a set of instructions about how to use it, and how to store it. However, the jacket is now obsolete, despite being made as recently as 2000, and being considered to be cutting edge in technology at the time. The connectors were all for outdated devices. Nowadays, electronic connectors are different, so this jacket could not be used anymore, even if someone wanted to.

In 2002, Bradley Quinn tried to precisely define techno fashion, although his expansive definition demonstrated how enormous and complex techno fashion can be: ‘The new wave of intelligent clothing that fuses fashion with communication technology, electronic textiles, and sophisticated design innovations that express new ideas about appearance, construction and wearability’ (Quinn, 2002, p. 5). Quinn’s definition showed that there is no single, specific style attached to techno fashion, but that technology becomes another tool for the designer to create something new and different.

Using Quinn’s understanding of techno fashion, we can see that the Levi’s jacket meets two of his criteria: it fuses fashion with communication technology by wiring a phone to the jacket; and it expresses a new idea about what fashion is, and what its function is, by making the jacket have another function other than just covering the body. The jacket becomes a chimera between an electronic device and a normal jacket, yet it is still a garment, it is still fashion.

After the collaboration between Osti and Phillips, a new trend in fashion developed. Science and technology studies sociologist Sherry Turkle discussed this in her book The Second Self, arguing ‘the trend was for new computational objects-personal digital assistants (PDAs), cell-phones, laptops-to become even more intimate partners to their users, more like thought-prosthetics than simple tools’ (Turkle, 1984, p. 3). We can see Turkle’s thinking reflected by the fact that Levi´s continued to search for further collaborations after this one where they could integrate electronics to their garments.

“The jacket becomes a chimera between an electronic device and a normal jacket, yet it is still a garment, it is still fashion.”

Levi’s latest collaboration with Google in 2018 could certainly be considered a remake of ICD+ collection: The Google Jacket (Figure 5 and 6) allows the user to connect their mobile phone to a denim jacket, which is made possible due to a small integrated computer in one of the cuffs. As a result, the jacket can be used as if it was a mobile phone. Through the jacket, the wearer can control features such as playing music, taking pictures, searching the internet, or following instructions from Google Maps, among many other features (Jaquard, 2019, p. 3). The jacket is sold in two different models for a price of around £200.

The more I researched about this new category in fashion, the more I realised that it is a far more complex field than I imagined. I also realised that there is not one exact way of making a techno fashion garment, nor a specific purpose. This is a new field, and most of the garments being created are experimental, which means that they can have any purpose and can be seen in any style. Ultimately, this made me understand that techno fashion is not a temporary fashion, it is a new way of creating fashion, through the use of technology.

Bibliography

- Facchinato, D. (2016) Ideas From Massimo Osti. Mantova: Publi Paolini.

- Quinn, B. (2002) Techno Fashion. Oxford: Berg.

- Turkle, S. (1984) The Second Self: Computers and The Human Spirit. London: Granada.

- Invisible Men Exhibition: An Anthology from the Westminster Menswear Archives. (2019) Available here. (Accessed 01.07.2020)

- The Register (2000) Levi's and Philips Create Wired up Clothing. Available here. (Accessed 01.07.2020)

- University of Westminster (2020) Westminster Menswear Archives. Available here. (Accessed 01.07.2020)

- VHM (2000) 2000 PHILIPS/LEVIS ICD+. Available here. (Accessed 01.07.2020)

All I want is...

All I want is...