In my dissertation, I explored the New Age Traveller movement, specifically focusing on the music and arts collective ‘Spiral Tribe’. I also examined the media representation of the movement through popular culture studies and music theorists, as well as fashion theory. Alongside fashion literature, archival image and magazine research, I engaged with my own practice to inform my argument, ultimately demonstrating that New Age Travellers were representative of a necessary show of defiance to mainstream media and law, and resulted in a new way of living, which is still seen to have an impact on lifestyles today.

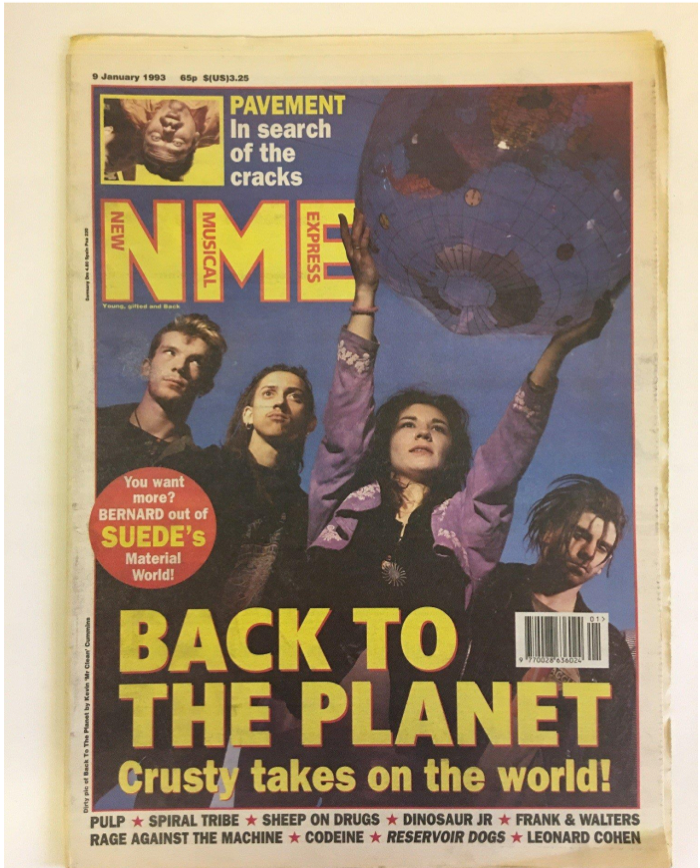

I visited the British Library to make use of their archives, trying to locate material around the New Age Traveller movement, and the band Spiral Tribe, in particular. In the edition of NME in Figure 1, published on 9 January 1993, there is an interview by music journalist Stephen Dalton. In this edition, the anarcho-punk band Back To The Planet were the front cover stars, suggesting a theme of counterculture that pervaded the NME, at least throughout the early 1990s. Alongside this, apparently authentic or ‘true’ indie bands such as Pavement and Suede, are also mentioned on the cover.

“New Age Travellers were representative of a necessary show of defiance to mainstream media and law, and resulted in a new way of living, which is still seen to have an impact on lifestyles today.”

The NME, however, rejected any attempts to understand or engage positively with the New Age musical movement. Writers such as Steve Lamacq dismissively asked, ‘who wants to stand in a field at a rave miles from anywhere when you can be at a gig with a roof?’. Critics during the same time explained, ‘the people who were writing about house music were viewed as a bit weird’ (Long, 2012, p. 180).

This kind of thinking may help us to better understand the hostility inherent in the article about Spiral Tribe in the NME, with Dalton describing the Tribe as lost in ‘crusty techno’ in the lead paragraph, creating a negative subconscious bias towards the tribe, as well as their aesthetic (Dalton, 1993, p. 1). However, the use of the word ‘crusty’ may only be seen as negative to certain individuals – many of whom were the demographic of NME, which at the time was mainly ‘white middle-class students'’ (Long, 2012, p.181). This readership was not the working-class, South London youth, who were predominantly associated with Acid House, and fans of Spiral Tribe.

Further in the NME article, Spiral Tribe are described as ‘instantly likeable’, but this is quickly followed up by Dalton commenting on their appearance: they looked like ‘skinheads…extras from Alien 3’ (Dalton, 1993, p. 1). The comparison with Alien 3 connotes an out of this world aesthetic that could certainly be accurately applied to this group. However, I also argue that this could seem threatening when coupled with the term ‘skinhead’, due to the violence often associated with this earlier British subculture. Later in the same article, Dalton focuses on the appearance of the Tribe further, sneeringly describing them as ‘dressing like a Hare Krishna fighter pilot’. The use of a religion as a derogatory description feels outdated and offensive to the modern reader (Dalton, 1993, p. 2).

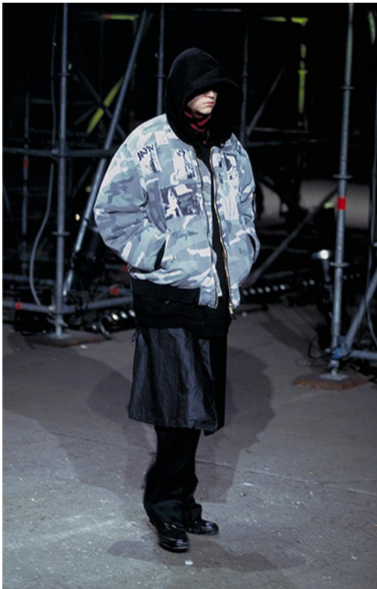

A photo taken from a Spiral Tribe video interview in figure 2, displays what seems to be a suggestion of a uniform worn by its members. This uniform consists of a bomber jacket, hence the comparison to fighter pilots by Dalton in NME. It is hard to tell whether the black jacket with white and grey shapes is hand painted, but I am convinced that it is, due to the fact that very similar patterns, especially the spiral, were often seen on Spiral Tribe flyers, and at free festivals. All members in the photo show a strong unity in their clothing by wearing such similar outfits. The simplicity of the outfits is far removed from those that would have been worn in clubs such as Shoom or The Hacienda, for example. The jackets, trousers, and t-shirt are far less colourful and there are fewer accessories, clearly defining a counter cultural difference, with Spiral Tribe being more ‘twenty-four seven’ ravers (Colin, 1998, p. 203).

The bomber jackets worn by the band implies power. This garment was originally made by Alpha Industries in the 1950s for the Air Force, and was manufactured and designed specifically to be both durable and insulating (Herm, 2018, p. 164). The garment was later appropriated and worn by Skinheads in order to stand out in fashionable terms. With its masculine, baggy shape, and connotations of readiness to fight, it implies both power and authority. The bomber jacket was worn by Spiral Tribe, as well as many other ravers, due to its durability and practicality, and furthermore, it connects clearly to the Tribes' anti-consumerism stance. It is interesting to note that this was prior to designers such as Raf Simons and Helmut Lang bringing the bomber to high-end fashion catwalks. Simons’s 2001 Fall/Winter collection titled ‘Riot Riot Riot’' featured bomber jackets throughout, with heavy layering and hoods, to create menacing figures.

The commercialization of the bomber jacket not only supports the Bubble Up theory proposed by Thorstein Veblen in his book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899 [1997]). But it also lessens the countercultural credibility of the bomber jacket, and makes it appear as more of a marketing tool used by the fashion industry. This is proven by a 30% increase in sales after American rapper Kanye West was pictured in a personalized Alpha Industries bomber, with high street retailers Topman, Zara and H&M cashing in on this new trend (Hypebeast, J. Cruz. 2016).

In summary, my dissertation examined the New Age Traveller movement that came to fruition in the 1990s, through fashion and lifestyle, in order to understand current day practices of activism, and alternative, music-based communities. I analysed rave culture, and zoomed in on its class history and political context from the 1970s to the present day, and considered alternative community cultures from a Cultural Studies perspective. Through drawing from a wide range of sources, my work contextualized the New Age Traveller movement, presented a case study approach to the Spiral Tribe, and embedded this within a material, political, economic, and cultural landscape. This was all supported through my own studio practice and understanding of garment construction.

Bibliography

- Collin, M. (1998) Altered States, The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House. London: Serpent's Tail.

- Cruz, J. (2016) ‘A Brief History of the Bomber Jacket: From the Cockpit to the Runway’, Hypebeast, Available here. (Accessed: 5th February 2020).

- Dalton, S. (1993) 'Spiral Tribe: You Can't Beat The System!', NME, 9th January.

- Friederike Herm, H. (2018) 'From Air Combat To Youth Culture and The Catwalk' in Rogger, B., Voegeli, J., and Widmer, R. (eds.) Protest: The Aesthetics of Resistance. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, pp. 163-165.

- Long, P. (2012) The History of The NME: High Times and Low Lives at The World's Most Famous Music Magazine. London: Portico Books.

- Veblen, T. (1899 [1997]) The Theory of the Leisure Class. Project Guttenberg, Online. Available here. (Accessed 27th June 2020).

All I want is...

All I want is...