The punk movement is an iconic British subculture. However, confusion often surrounds what the punk movement actually meant. It is important to understand what made punks so successful in being noticed, and to question whether it was the subculture itself, or their wrongful representation, that created society’s negative attitudes toward them. Their fashions give valuable insight into this.

Punk fashions can be understood as a unique expression of the self. However, much media coverage described their style as visual violence. The rips and tears in their clothing were translated through media representation as aggressive, and creating fear amongst older generations. Whilst how punks dressed was undoubtedly a political stance, bolder imagery such as the Swatstika was more a way to ‘shock and confront rather than associate with right-wing organisations’ (Arnold, 2001: 43).

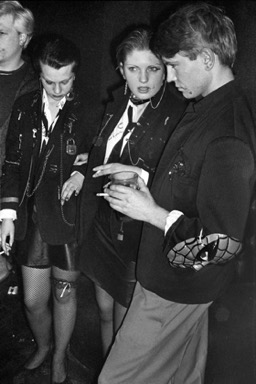

The Swatstika was originally connected to Buddhism as the symbol of luck and peace (See Figure 1). However, punks later adopted it as the Nazi ideology of violence and disruption, tarnishing the lighter attitude of the movement. Roland Barthes stated that ‘it is not the object but the name that creates desire; it is not the dream but the meaning that sells’ (Barthes, 2005: 128). Barthes’s deconstructive semiotic approach implies that garments convey what the wearer wishes, and signifies a social class. Therefore, punks may have used symbols on garments to act as signifiers for their dissatisfaction with social life, and to demonstrate their rebellious, working class attitudes (Figure 2).

If this is the case, onlookers might subconsciously assume what is imposed as signified to be true. However, when relating this idea to punk, it wasn’t what they expressed through fashions but what was written about them that was seen to be true, showing that the true value behind an object or individual is an entirely elusive concept.

My Dad’s friend, Tomas, identified as punk from eighteen years old, and he still styles his hair in a giant Mohawk, and wears embellished and hand-painted leather jackets, suggesting that punk is his way of life. Figures 3 and 4 are photographs of his jacket. He says it ‘originally cost me 60 quid from Camden’, showing that punks still accessed normal retail stores, and that leather was used in many wardrobes, not just punk wardrobes.

The jacket features the anarchy symbol, hand-painting, chains, pins, studs and safety pins. These features demonstrate that Tomas transformed a jacket that was part of society’s norms, into an iconography of what he understood to be punk. Describing the handicraft of the jacket, he says, ‘I started to mess with it and get some influence from other punks’, suggesting that whilst there was a level of fun decorating his own belongings, there was an expectation to omit a certain attitude through clothing.

In A Drink with Shane McGowan, McGowan explains that after he joined the punk community, he faced regular violence from outsiders. He recalled how ‘punks were not afraid to fight back with anything they could’, including the ‘dog-chains and knives’ they wore on jackets such as this one (2001, p. 154). A punk openly admitting there were acts of brutal violence confirms that punks were victims of attacks, and fashion was used not only creatively as an expression, but was also a defense mechanism to store weaponry.

Dick Hebdige, in Subcultures, explores how style is a form of refusal and revolt. Hebdige references punks, describing them as ‘alternatively dismissed, denounced and canonised’ (1979, p. 2). Hebdige explains how mundane objects such as safety pins, take on a symbolic dimension to become a form of disgrace. These objects with double meanings signify the tensions between dominant and subordinate groups, as these subordinates’ appropriated simple objects to carry secret meanings. Style in subculture then defyies nature, and kick starts a visual disgust towards punks through using gestures to move towards speech in order to offend the silent majority and challenge the principle of unity and cohesion.

“punks were victims of attacks, and fashion was used not only creatively as an expression, but was also a defense mechanism to store weaponry.”

Subcultures use fashion as detachment from the mainstream, and plays on the idea that ‘consumers are often very deliberate, knowing and purposeful; they actively decide certain consumption practices for particular reasons and to achieve certain outcomes’ (Horton/Kraftl, 2013, p. 67). This disruption of a transient society causes this particular youth style to deteriorate perhaps more than any other subculture, mainly due to the idea that they were adverting change through garments and ‘humble objects’ that the public saw as normalisation.

Having said this, in The Fashion System, Roland Barthes identified a flaw, explaining that when a ‘description accompanies a photograph…from that description it gets its structural unity’ (1990, p. 55). Focusing on this ideology in relation to the subculture, the media, as well as the written words on punks clothing, initiated a snowball effect that made punk synonymous with anarchy and violence. Whether negative or not, their fashion became far more consistent because of it and began defining a sole image of what punk was.

‘After visiting the Bishopsgate Institute Archive, I read through the diary dating from 1979 until 1983 of Phillip Munnoch AKA Captain Zip, a punk. It gave me an insight into what being a punk day to day was really like. Whilst Munnoch wrote political slogans such as ‘this planet will get nowhere while the talented are prevented from ascending’. (Munnoch, 1979: 28), I was astounded to see his descriptions of the punk clothing he wore, and how it made him feel wearing them. The descriptions demonstrated that punk clothing was much more than an expression of violence, but was also was an expression of the self. The punk style, according to Hebdige, was a ‘paralysed look and petrified quality…found a silent vote in the smooth moulded surfaces of rubber and plastic, in the bondage and robotics which signify punk to the world’ (1979, p. 69). However, Phillip Munnoch wrote in his diary that he wore rubber pants for several days because they were ‘comfortable’, thereby suggesting that punk fashion found refuge in the strange and diurnal desires.

Malcolm Barnard argued that ‘what is important is the ‘person’ or the ‘real person’ beneath or behind the ‘mask’ of fashion” (2014, p. 13). This raises two key ideas about punk fashion: Firstly, if their fashions were a ‘mask’, then what do we expect to see of the ‘real person’ and was what they stood for a part of their costume, the violence and the destruction acting as an outer shell whilst those youths hidden underneath were normal people? I think garments can act, as Barthes theorises, as a signifier for what a person wants to communicate. However, I am not convinced that fashion acts solely as a ‘mask’. Surely it is more complex.

“punk clothing was much more than an expression of violence, but was also was an expression of the self”

If we consider this, then are punks reflecting an association with violence as part of their inner self, or is this ‘mask’ used as a defence mechanism to keep the masses away. Without a ‘mask’, this would simply mean that social order had disappeared, and what gets left is a purpose for fashion to mirror our own selves.

Through archival investigations, extensive secondary literature research, as well as oral histories, I explored a material, personal, and nuanced history of the punk movement in the UK, placing it firmly within the political, social and economic context of the time. My dissertation engaged with subcultural theorists and critiqued this work, as well as critiquing the popular misconceptions around the punk subculture that emerged in the 1970s, and from a contemporary perspective. My dissertation assessed how consumption practices and DIY culture were crucial to punk style, and through this, I considered the ways in which punks crafted their identities through community engagement, and anti-Capitalist political sentiment, ultimately arguing for an alternative history of punk and punk style.

Bibliography

- Barnard, M (2007). Fashion Theory: A Reader. Routledge: London

- Barthes, R (1977). The elements of Semiology. Hill and Wang: New York

- Barthes, R (1990). The Fashion System. University of California press: California.

- Diary of Phillip Munnoch aka. Captain Zip, dating 1979-1983, Bishopsgate Institute Archive.

- Hebdige, D (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style (New Accents). Routledge: London

- Hebdige, D (2011). ‘Bleached Roots: Punks and White Ethnicity’ in Duncombe, S and Tremblay, M (ed.) White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race. Verso Books: London

- Horton, J, Kraftl, P (2013). Cultural Geographies: An Introduction. Routledge: London

- Link (accessed 08-12-19)

- Link (accessed 04-01-20)

- Link (Accessed 10-02-20)

All I want is...

All I want is...